Jason Warr

“For the first time in my criminology degree I can actually see the theories and ideas in my own life, outside, in the street.” (Final Year Criminology student, module Feedback (shared with permission.)

Autumn Term. University of Nottingham. 2023. For the first time in the UK I taught a full elective module on Sensory Criminology. Aimed at final year Criminology, Sociology, and Liberal Arts students the idea was to introduce students to the complexities of revisiting the criminological canon through considering the varying ‘sensoria’ that shape our experiential reality and understanding of the world. The basic point being that we, as human beings, are sensory creatures, we smell, we touch, we hear, and we see. These elements of our experience fundamentally shape not just our realities but, necessarily, how we experience and understand issues of crime, victimisation, and criminal justice.

Designing the course was one thing, selling it to students (and other staff members) who had not encountered such ideas before was something quite different. How do you convince students that smell can play a profound role in the experience of victimhood and criminal investigation when they have never really considered the idea of smell in their own lives? What of chronoception and the passing of time in terms of routine activities or sound in relation to green criminology? With developing the module came an explicit awareness that I was going to have to ask students to think about their studies in significantly different ways, and to challenge their learning as they had never considered. I was worried that they would not come with me. I was worried that challenging their pre-existent/nascent ways of criminological and sociological thinking, and asking them to develop a new criminological imagination, was going to go properly Pete Tong.

I need not have worried.

In terms of selling the module it very rapidly became evident that students ‘got’ it. Prior to running the module, I was explaining the basic concepts to a group of students and explored the rather silly, esoteric, and narrative convention of the ‘smell of fear’. I posed the equally silly question, “Does fear have a smell?”. Given this is a common phrase it seemed a useful place to start. Most of the students mentioned ‘acridness’ bitterness’ or sharpness (terms often used to describe this sensory marker of emotion in literature), but one student, a young Black woman from East London, laughed and went “sure, the absence of cocoa butter!”. The other Black students laughed; they immediately got the joke (both about Black skin care and being Black in white spaces), others just looked baffled. However, what it made clear was that students, even those not necessarily engaged or interested in taking the module, could see the links between complex socio-political concepts and the material, corporeal world in which they existed. Simple.

Not so simple …

I designed the module to cover a wide range of quite complex topics, which brought together both classic and novel criminological literature and, to continue the piracy of criminology as a rendezvous subject, coupled it with both novel and challenging sensorial anthropological and sociological developments. At its core, the module focused on the sensory through three distinct issues: 1. The communicative functions and symbolic interactionism of sensory experience; 2. The sensory/emotion/context divide; and, 3. The practices of thick description. There were two assessment points. The first assessment asked students to explore a sensory experience descriptively and analytically. The idea being to explore the complexities of communicating the interiority of sensory experience through written text. The second assessment asked students to sensorially examine a specific ‘space’ of their choosing. The aim was to think through research methodologies, ethics, and forms of analysis that go beyond the subjectively perceptual. Both assessments were designed to allow students to be creative in writing and thinking. By the end of the module students would have an understanding of:

- The history of sensory social science

- The development of sensory criminology

- Sensory criminology and the philosophy of the social sciences

- Methods of sensory research

- The ethics of sensory research

- Differing sensory studies in penality and criminology

- How sensory criminology can challenge traditional criminological theory

- Sensory victimology

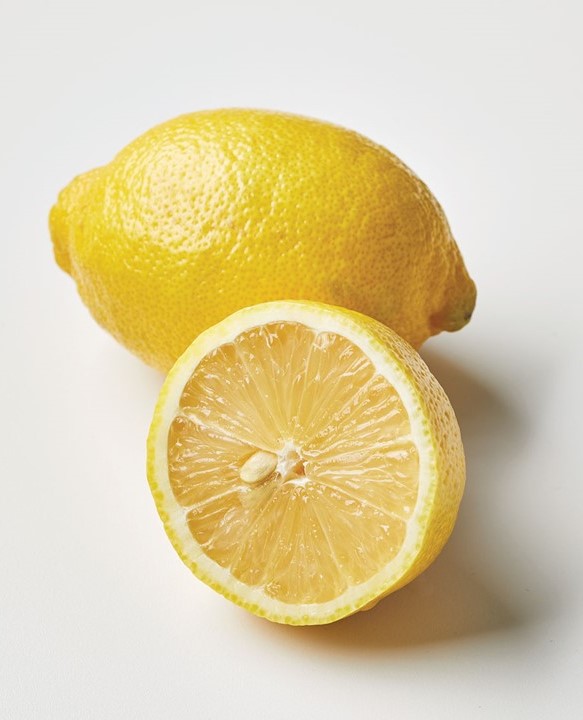

Perhaps the most interesting but complex element of teaching the module was to get students to think through both the distinctions between the Senses, the relationship between them (intersensoriality) – especially as this relates to interoceptive (internal body states) and exteroceptive (external stimuli) senses and the shared yet often subjectively interpreted experience of sensescapes. Think about hearing a police siren – the intepretation is both singular and communal. This is distinct from the emotions that the sensory can evince and how we often substitute emotive descriptors for sensory ones when talking about the experience of sensoria, and the relationship between these issues and the spatialised/relational contexts in which said senses and emotions are being evoked. This is a core element of sensory criminology – affect and the sensory are distinct and to collapse them into a singular framework is to miss the point (and an entire world of analysis). Yet this is common to written English. To make the point, in the first seminar, I invited students to eat a lemon at the same time (I made sure no one was allergic) and then to write a few sentences describing the experience … but they could not use the words ‘bitter’, ‘sharp’, or ‘sour’ (seriously, try this, it’s not easy). Once those word options were removed, most students fell back on the same emotional signifiers (highlighting the degree to which the experience was shared) to explain the experience yet acknowledged that this did not really capture the reality of the sensation experienced. That was the way in.

One of the core problems of developing a sensory criminology is that many scholars have just not got it. They have either attempted to reduce it to something it is explicitly not (affect studies or embodied phenomenology – these are distinct fields in and of themselves) or, by ignoring the symbolic and material communications inherent to sensory experience have dismissed it as descriptively superficial. It has been interesting to see scholars who pride themselves on being analytically open-minded fail to escape the buttressed borders of their entrenched epistemic and methodological schema. They have clutched these comfort blankets so firmly that they cannot stretch a criminological imagination rendered brittle by repeated, but narrowly focused, use. This was not true of the students on the module. It has been a pleasure to see them open mindedly grapple with, and question, the complexities of trying to disentangle and understand criminological sensoria. This was evident in getting the students to think through the Sensory > Emotion <> Context problem.

The Sensory > Emotion <> Context problem, in many ways, sits at the heart of teaching (and understanding) Sensory Criminology. The problem itself is fairly easy to explain but demands a complex, multi-level, degree of analysis/explanation of any sensory event in order to capture it. So, what is the problem: it is that the sensations we experience communicate information that necessarily evokes emotional and cognitive responses, but both the communicated information and those subsequent emotional and cognitive responses are inherently contingent on context. The same sensation can therefore evoke varying responses dependent on differing settings. Take, for instance, hearing footsteps in the dark (a theme raised across all seminar groups by a wide number of female students) or seeing the blue lights of emergency vehicles. The emotional response to each of these can be utterly contextually contingent. If you are a young woman walking home alone from a club, the timbre of the sound of footsteps can utterly change the response (i.e. rushed heavy tread as opposed to the click clack of high heels), as can directionality (towards or away), or even proximity to a ‘safe’ space. To understand these experiences, at a minimum, we need to consider issues of time, space, geography, locale, gender, power, relations, company, rhythms, activity, sound localisation, temperature, lighting, history, weather, and much, much more. Without much prompting the students got it, and immediately understood how this related to other criminological issues they had been studying (from causal models of crime to victimology to green/environmental issues to state crimes), and what it meant for thinking through a seemingly simple issue. It also allowed them to think through criminological concepts as they related to their own lives and experiences.

It was this ability for students, regardless of lives lived, to ‘see’ the topicality beyond the materiality of the classroom and apply the ideas, which allowed them to grasp and utilise the concepts in quite complex ways in the assessments. As third year students you would expect this to be standard, but even at this level getting students to engage and have the confidence to apply new ideas can be difficult. We over-assess students (and children more broadly) in ways that is, pedagogically (and emotionally), detrimental. This requires a sector wide conversation – not that this will be possible whilst we have an educationally ignorant Government. Anyway, the first step in doing this was in seminars where I would repeatedly ask students to both think through how you communicate a subjective sensory experience and to then analyse it. This led us to Geertz’s ‘thick description’. The purpose here was, in seminars and in preparation for the first assessment, to describe quite simple (non-criminological) sensory experience in as much, and as rich, detail as possible in order to communicate the sensation, and its context, in such a way as that someone not experiencing it, would be able to (to create a form of verstehen).

This was designed to do three things: first, allow students to develop their writing in creative ways (something the modern university actively and pedagogically discourages) and to explore the interiority of their experience; second, to consider their audience (beyond a marker) and what the communication of that interiority can involve for others; and, third, to begin to consider how the sensory and experience can be turned into data that can be analysed. This was the goal of the first assessment; to describe a sensory experience in five hundred words, and then analyse that piece of writing (1,000 words). Writing in terms of what is known about sensory studies and how that could be related to wider sociological/criminological issues. For instance, one student wrote about their morning coffee and the role of smell and taste in social routines; another spoke about perfume and scents and their link to familial relations and homemaking; others wrote on connections between the sensoria of clubs, the carnivalesque, and deviant leisure. The writing was rich, the detail profoundly communicative, and the skills on display impressive.

The first half of the module and assessment focused on the relationship between the subjective and the communal as it related to understanding and analysing the sensory. The latter half focused on the spatial and the criminological. This gave students the opportunity to apply skills developed in the first half of the module to the criminological analysis of space. I encouraged students to understand those Lefebvrean notions of space and place, and how the sensory may provide new ways to do this if applied to criminological issues or theory. For instance, could we explore sound, rhythmanalysis, and Routine Activity Theory? Does Guardianship (or its absence) have an audible quality? May the acoustic rhythm of a space play a part in the decision making of those who commit crimes in that space? What about Labelling Theory? Does scent and smell play a part in the way we marginalise and label others? If so, how, why, and what communication is being conferred that allows for this? Can this analysis be applied to Racist logics and policing? The possibilities and combinations of this were endless and gave students a way into a canon that had, until that point, seemed abstract.

The results in the final assessment were testament to the students grasp of rich, thick description, criminological theory, concepts of space/place, and application of a sensorial analysis. One student wrote, vividly, on how the sights, smells, sounds, and textures of Las Ramblas in Barcelona create a polyrhythmic environment that in and of itself creates criminal opportunities in ways not applicable to other urban spaces. Another wrote about the front door as a portal and the relationship between arrythmia and household routines as they may relate to crime. Others wrote about traversing the urban night-time economy and the way sounds, and their absence, can contribute to the gendered fear of crime. There was explorations of parks, lanes, alleyways, shops, pubs, kitchens, public toilets, and carparks. Topics of hate, VAWG, violence, theft, drug dealing/taking, policing, car crimes, and racism were covered. Criminological theory as disparate as Environmental Crime Prevention through to Drug Normalisation, and even Zemiology were considered, and unpacked. I know I am biased (and incredibly proud of my students – I told them this) but these were some of the richest and most critical student essays that I have ever marked (even if some did use Wilson and Kelling in rather odd, and unaware ways). The breadth of reading beyond the course material was impressive and extensive. I nearly got altitude sickness from some of the marks I gave (moderated and approved).

So, what did I learn form teaching Sensory Criminology for the first time? I had built quite a rapport with the students (I had 78) and asked them for quite brutal feedback … they took me at face value. Ouch. However, even in their critique it was evident that they had understood the pedagogy inherent to the module design and the aims of the module. They gave me useful advice on where the gaps in their knowledge and skills lay and how my assumptions about these issues had compounded their difficulties. In light of these comments, I will be adjusting some of my seminar tasks. However, beyond that, one of the things I learnt was that lecturer cynicism about students and their learning is really an ‘us’ problem, rather than a ‘them’ problem. It was clear from the start that students were both reading the set list ahead and backwards. They would raise concepts in discussions that we had yet to cover and were linking these to those covered earlier in the module. I have rarely seen that before. The students were taking ownership of their own subjective learning, despite the scaffolding of conceptual learning built into the module. I have not quite unpicked what it is about the teaching of the sensory that a) allowed for that; b) enabled them to interrogate and thus shape their own learning (oddly something similar to the disruption of ordering that is central to cognitive interviewing, a topic that we explored at various points of the module); and, c) to develop their reflexive learning, and pursue lines of interest through the module topics in ways that made sense to them (including the iterative process of revisiting texts when encountering new ones). If I can pin that down …